View from the window at Le Gras, 1826, Niepce.

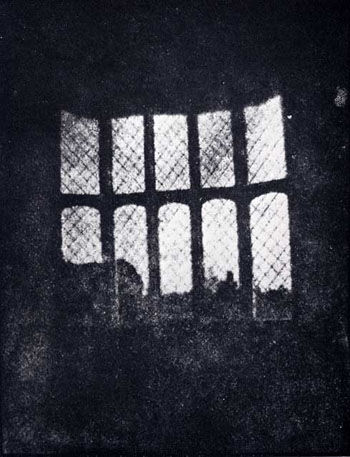

The window at Lacock Abbey, 1835, Henry Fox Talbot. Science and Society

Who came first depends upon the process. In 1826, Niepce produced ‘View from the Window at Le Gras’ which is described as the world’s oldest surviving ‘photograph’ made with a camera and was certainly the first permanent image. It was on a pewter plate and exposure took 8 hours. Daguerre developed what Niepce had begun, altered the chemistry and by 1839 began producing positive images which were one-off, used silver and were often extremely beautiful but couldn’t be used to produce commercial prints. Every one was different and unique. Henry Fox Talbot meanwhile was exploring the use of sensitised paper. His first paper negative was only an inch square and was made at Lacock Abbey in August 1835. Paper negatives could be used to prepare paper positives - in other words, prints. Soon the paper negative became a glass negative and photography took off. Within a very few years, photographers were out and about recording royalty, celebrities, war, the development of Trafalgar Square, the laying of endless railways, glorious landscapes, back street slums - as well as astoundingly elegant pornography - within forty years of the first negative, police raided a family business run from a house in Pimlico and seized 130,000 pornographic photographs and 5,000 glass slides.

Until 1862, there was no copyright in photography and when protection finally arrived, it was not a success. Promoters of the new bill thought photographers should be included with engravers and lithographers and clearly they were right but photographers decided they were different and at the last moment, joined painters in the Fine Arts Copyright Act of 1862 - which didn’t please portrait painters, paranoid about photographers who were taking away much of their business. The duration of the term of copyright in the new Act was a miserly life plus seven years. Engravers got life plus twenty eight years; writers got an option of life plus seven years or forty two years from publication, which was often longer. Since paintings are not ‘published’ they missed out and photographers were therefore excluded whether they liked it or not. Added to this disastrous act and perhaps because legislators believed photographers could not be trusted to refrain from filling their shop windows with photographs of the wives and daughters of the upper classes, which was considered vulgar, an added clause appeared that made the bill a calamity for those who were supposed to benefit. When any painting, drawing or negative was sold for the first time or if the work was commissioned, the seller could not retain copyright without a written agreement from the buyer. This worked both ways because the first time buyer had to get an agreement too. In fact, without an agreement, copyright didn’t belong to anyone and if the work was sold it passed into the public domain. Dealers purchased new paintings, retained copyright and sold the painting on but still retained copyright because this Act was only concerned with first time sales. Painters were embarrassed to discuss their rights with buyers and commissioners for fear of jeopardizing a sale, so a lot of paintings escaped. Photographers sold prints, not negatives and were not affected by print sales but they were commissioned and suffered from the same embarrassment when dealing with clients. The bill stipulated that once again, everything had to be registered with the Stationers Company. From the beginning the promoters attempted to put a stop to this ill conceived bill but were dissuaded by the House of Lords on the grounds the anomalies could be ironed out later and the Act did include some benefits to painters. ‘Later’ proved to be 1911.

The 1911 Act gave photographers rights in their work for fifty years from the end of the year in which the photograph was taken which seemed a bit churlish because writers and artists got life plus fifty years but at least it was no longer necessary to register everything with the Stationers Company. Photographers who were commissioned were not considered to be ‘Authors of their own work’ They had to wait until 1988 for that. One aspect of the UK Copyright Act 1911 was that it abolished common law copyright which was all the bits which everyone assumed were law because that was the way they had always been. The new Act organised everything according to the book, a comprehensive act designed to replace the mess of different copyright acts which had existed before and to get rid of the anomalies. It came about because of the Berne Convention 1886, an agreement to honour the rights of authors who were nationals of every country which had signed the convention. Nowadays this is a formidable list although this was not the case then. The 1911 Act didn’t change everything. Some of what was in the previous acts was absorbed into the new one. St Columba and the psalter was still there - ... any copy of a work made or imported in infringement of the owner’s copyright is the property of the owner ... to every cow her calf, to every book its copy There were however big problems which continue to be big problems. The owner of the negative of a photograph at the time when such a negative was made shall be deemed to be the author of the work. Who owned the film? Often it was the photographer. He had done what he wanted to do because he felt like it and for his own benefit but if he was commissioned, he didn’t own the copyright unless there was a clearly understood agreement to the contrary. The commissioner owned the film and the copyright. If the photographer was employed, his employer acquired the copyright - and still does. Regardless of what he photographed or where he photographed it, unless he was sufficiently bullish or important and could insist otherwise, a photographer had no claim on copyright if work was done in the course of his employment. It was thus in 1911, it’s the same now and it still causes hassle. The 1911 Act, which became law on 1 July 1912, stumbled on over the years with the odd tweak here and there as new things were invented and two world wars muddied the waters. It was this Act which made it a requirement that copies of every UK book, journal, newspaper and magazine should be lodged with the British Library. There were five other libraries entitled to copies but they had to claim a copy. The British Library got copies regardless and still does.

The Copyright Act 1956 repealed the 1911 Act but kept bits of it. The term of protection became fifty years from the end of the year in which the photograph was first published and thus introduced perpetual copyright in anything which never got on the page. The Act became law on 1 June 1957 and carried over the provisions of the 1911 Act by continuing to limit to fifty years copyright protection in photographs taken before that date whether published or not. Thus, a picture taken on 31 May 1957 but never published was out of copyright on 1 June 2007 but a photograph taken the day after would be in copyright for ever - or until it did finally get published and then it won another fifty years from that date. Ownership of copyright was still in the hands of the commissioner or whoever owned the film at the time the photograph was taken and employers continued to retain copyright in all work produced by their employees during the course of their employment.

The 1988 Act was a new broom sweeping clean. This time, when the first draft of the Act was published, determined photographic associations and several concerned individual photographers read it carefully and started lobbying - and it worked. The original intention was that anything which constituted the reporting of current events should be considered fair dealing but it was pointed out that most photography is ‘current events’ if the circumstances are right and photographers would be ruined. The magic words (other than a photograph) complete with brackets was added to section 30(2). There were other alterations to the original draft which just goes to show that lobbying works and when the Act became law on 1 August 1989, it finally recognised that photographers were artists, had rights and were the authors of everything they did regardless of whether it was commissioned or not. Commissioners lost out. Photographers got fifty years from the end of the year in which the photographer dies, they got moral rights, they got the right to object to someone retouching or cropping their pictures, they got the right to a credit - in fact, they got nearly everything they wanted. The Act also did away with perpetual copyright by limiting protection for everything taken between 1 June 1957 and 31 July 1989 to fifty years from the implementation of the 1988 Act - that is, the end of 2039.

What they didn’t get was rights for employed photographers. They got nothing. Their employer owned copyright in everything unless the photographer could persuade them otherwise and despite several changes since, that is still the way it is. Commissioners of photography fought back. The day the Act became law, many photographers found envelopes in the post from their regular commissioners containing a £1 coin, acceptance of which constituted a total assignment of copyright in everything done for the client in perpetuity! Failure to agree would mean no further commissions. Many photographers considered this to be an absurd joke, pocketed the money and carried on regardless although this wasn’t a good idea and created difficulties later. It didn’t stop the commissions coming because the photographers targeted were on the whole the magazine regulars and commissioners discovered that lesser mortals were less reliable.

The 1988 Act has since changed yet again. The EU love Directives and confusing new ones affecting the Act have appeared regularly since 1992. Applying their usual principle - that everything in every EU country should be harmonised, they decreed that the same term of copyright should apply to everyone and since it wasn’t a good idea to reduce the term of copyright protection anywhere and Germany already had seventy years, on 1 January 1996 the UK changed the term here to match everywhere else and we now have seventy years from the end of the year in which the photographer dies. All photographs taken during the period of perpetual copyright from 1 June 1957 and still unpublished before 1 August 1989 had already won themselves copyright protection until the end of 2039. Now, copyright will expire seventy years after the death of the photographer. If the photograph was published before 1 August 1989, expiry is the end of the year of publication plus fifty years or the end of the year the photographer dies plus seventy years, whichever is the longer It’s confusing and messy but it works.

Where copyright is concerned, it’s always history because it evolves day by day. Nothing is for ever.